After the painful process of implementing a BPE tokenizer (and optimizing it), I hit this question: Should I train it exclusively on my training data?

Every ML course I've taken forbids using the validation set for pre-processing, yet I couldn't find any papers testing this, so I decided to investigate myself.

My goal was to learn what, specifically, goes wrong if your tokenizer is trained on validation data and whether it introduces a bias that inflates performance.

I ran controlled experiments (30M–125M LLaMA-style) and found no measurable bias from training the tokenizer on training + validation when data is large and diverse.

Experimental Setup

To isolate the impact of this choice, I designed a controlled experimental setup. The goal was to measure the precise downstream effects of training a tokenizer on data that includes the validation set.

Dataset: OpenWebText Subset

I used a pre-processed subset of the OpenWebText corpus, which is large enough to exhibit meaningful trends but lightweight enough for rapid experimentation.

To simulate a realistic leakage scenario, I re-partitioned the original dataset:

- Training Set: 80% of the original

train.txt. This is the primary data for training the models. - Validation Set: The remaining 20% of the original

train.txt. This is used for validation during model training. - Held-out Test Set: The original

valid.txt. This set remains completely untouched by either the tokenizer or the model during training.

| Split | # Documents | Token Count (M) |

|---|---|---|

| Train | 80,000 | ~ 45.1 |

| Validation | 20,000 | ~ 11.3 |

| Test | 20,000 | ~ 11.2 |

Table 1: OpenWebText subset statistics after split and tokenization. Note that both tokenizers lead to the same number of tokens.

Tokenizer

Implementation:

As I mentioned before, this whole question popped up when I was building my BPE tokenizer, so I will briefly talk about how I implemented it since this is the version I used for all experiments.

For those unfamiliar, BPE is a clever algorithm that builds a vocabulary by starting with individual characters and then iteratively merging the most frequently occurring adjacent pair of tokens. For example, if e and r appear together often, BPE might create a new token er. It keeps doing this until it reaches the desired vocabulary size.

Building it myself allowed me to control every little detail and observe the process up close.

Here are a few key design choices I made:

- Pre-tokenization: Before BPE can merge pairs, the text needs an initial split. I borrowed the regular expression pattern from GPT-2. It's great at intelligently splitting text into initial chunks of letters, numbers, and punctuation while correctly handling whitespace.

- Tie-Breaking: To ensure my tokenizer was deterministic, I implemented a simple tie-breaking rule: pick the pair that is lexicographically greater, comparison is done on the actual string and not in the bytes.

- Optimization: I parallelized the pre-tokenization step to run across multiple CPU cores and, more importantly, I implemented an incremental merge algorithm that avoids rebuilding the frequency counts from scratch after every single merge.

The performance boost was huge. The optimized version was nearly 10 times faster than my initial attempt.

| Version | Pre-tokenization | Merge Strategy | Runtime (10k docs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Naïve | Sequential | Full dictionary rebuild | 3.1 s |

| Optimized | Parallel (4 threads) | Incremental frequency update | 0.34 s |

Table 2: Tokenizer implementation runtime comparison.

I include all the implementation details and code with profiling and benchmarking in this repository The repo also contains the exact scripts used to produce the tokenizer artifacts used in these experiments. I also have a separate blog post talking about the engineering details here.

Training:

With a fixed vocabulary size of 32k, I trained two separate Byte-Pair Encoding () tokenizers using a custom, optimized implementation.

- Tokenizer A (The "Clean" Tokenizer): Trained only on the new training set. This follows best practices.

- Tokenizer B (The "Leaky" Tokenizer): Trained on the new training set plus the validation set.

Both tokenizers used the same hyperparameters for merges, pre-tokenization, and normalization. The only difference was the set of source documents passed to the BPE trainer.

The core of the experiment is to compare the downstream performance of models that use these two tokenizers.

Model Architecture: LLaMA-Style Transformer

To ensure the findings are relevant, I adopted a LLaMA-style decoder-only transformer architecture with the following design choices:

- RMSNorm for pre-normalization.

- Rotary Position Embeddings (RoPE).

- SwiGLU activation in the feedforward layers.

- Shared input/output embeddings.

I trained models of three different sizes to observe how scale might affect the results. I kept in mind best-practice hyperparameter ratios:

| Model | Layers | FFN Dim | Heads | Seq Len | Params (M) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small | 8 | 512 | 1365 | 8 | 512 | 30.1 |

| Medium | 12 | 768 | 2048 | 12 | 512 | 61.4 |

| Large | 16 | 1024 | 2730 | 16 | 512 | 124.6 |

Table 3: Transformer architecture hyperparameters.

Training Setup

All experiments were conducted on Kaggle, which meant I was on a tight compute budget with weekly quotas on GPU and TPU time.

Before burning through my hours, I did some back-of-the-envelope math to figure out the computational cost of different training configurations. The total number of tokens a model sees is pretty simple to calculate:

And to estimate the total compute needed in FLOPs, there's a handy rule of thumb from the Chinchilla paper:

I crunched the numbers for a few potential setups, assuming a 15k training, to see what was feasible:

| Context Length | Batch Size | Total Tokens | FLOPs (30M model) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 256 | 64 | 246M | |

| 512 | 64 | 492M | |

| 1024 | 64 | 983M | |

| 1024 | 128 | 1.97B |

Table 4: Estimated training compute across configurations using . I applied the same analysis for other model sizes.

To stay within the 16 GB of memory on each TPU core while still getting a decent throughput, I had to find a sweet spot. I settled on a context length of 512 for all models and scaled-down the batch size based on model size (64 for the 30M, 48 for the 60M, and 32 for the 120M model) to avoid OOM errors.

For the training itself, I used the AdamW optimizer with a custom cosine learning rate scheduler. I evaluated the model using an overlapping sliding window to get a more stable perplexity score.

Other training details in the repo: Mixed-precision training, per-client batch splitting used on TPU, checkpoint frequency, and Weights & Biases logging configuration.

Important:

All runs use a single seed due to Kaggle budget constraints; reported PPL differences are therefore single-seed estimates (see Appendix for variance discussion).

Hypothesis 1: Leakage Will Be Obvious in Tokenizer Metrics

My first hypothesis was that the leakage would be directly observable in the tokenization metrics.

A tokenizer trained on the validation data (Tokenizer B, leaky) should, in theory, be "better" at tokenizing it. I expected to see:

- Higher Compression: Tokenizer B should represent the validation text with fewer tokens, resulting in a higher compression ratio (more bytes per token).

- Different Fragmentation: Words in the validation set would be broken down more efficiently, altering the word fragmentation statistics.

- Greater Token Overlap: The vocabulary learned by Tokenizer B would have more in common with the tokens found in the validation set.

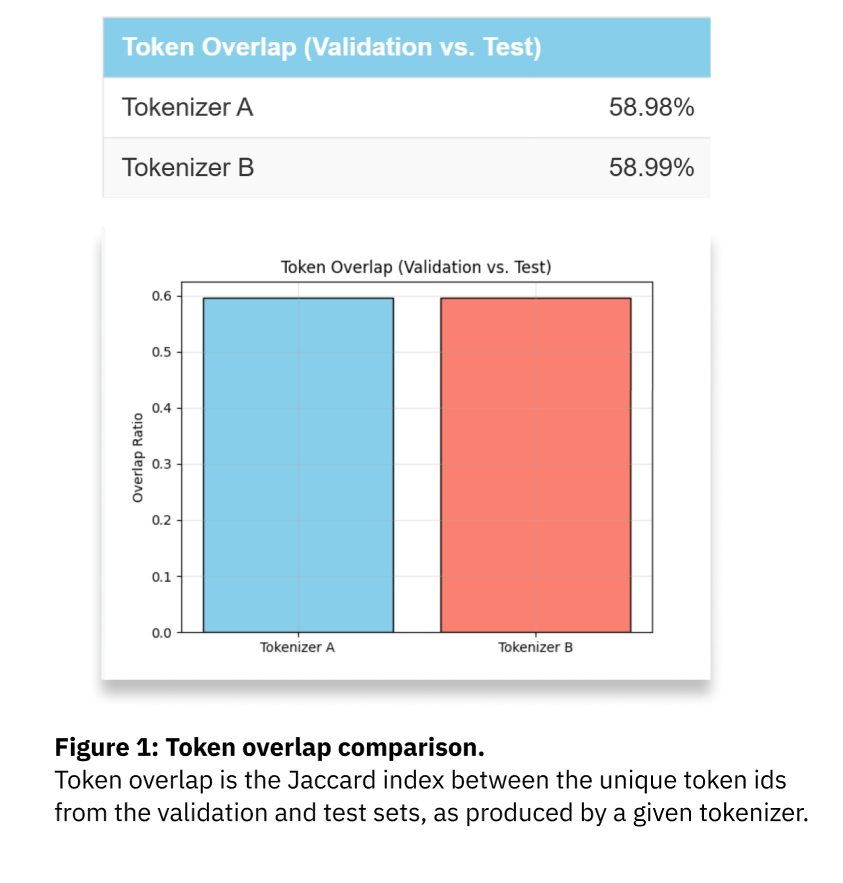

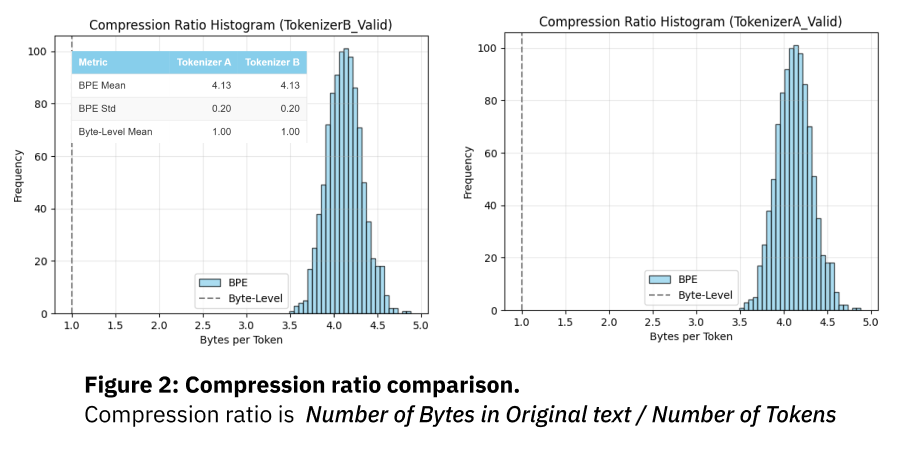

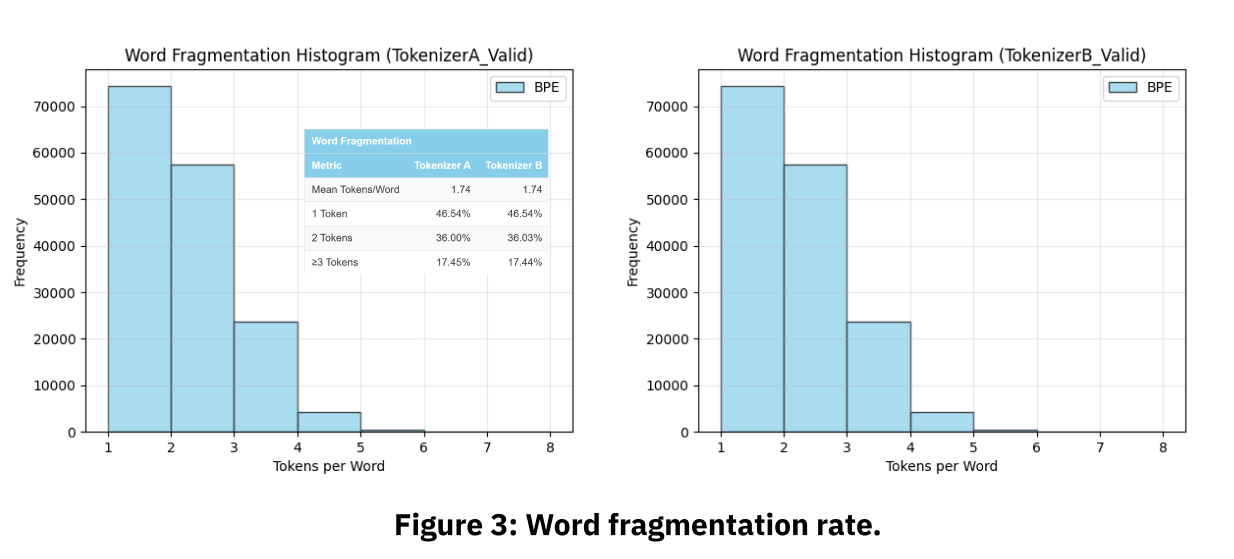

I ran a series of tests comparing Tokenizer A and B on the validation and held-out test sets. The results were that the metrics were virtually identical.

These results show:

- Jaccard overlap of validation and test sets: identical = 58.99% (Δ = 0.001).

- Compression ratio identical = 4.13.

- Word-fragmentation distributions indistinguishable within measurement noise.

TL;DR:

Including the validation set in tokenizer training did not produce a statistically significant change in compression or fragmentation. The validation set is simply too small and statistically similar to the training data to meaningfully alter the BPE merge rules. My initial hypothesis was wrong; the data leakage is more subtle.

Hypothesis 2: Leakage Affects Learnability, Not Representation

If the leakage isn't visible in the tokenization statistics, it must be more subtle. My second hypothesis was that the leakage affects a model's learnability rather than representation efficiency.

By seeing the validation data during tokenization, Tokenizer B supposedly creates a vocabulary that is ever-so-slightly "specialized" for it. A language model might then exploit these specialized tokens as a shortcut, achieving a better score on the validation set without genuine generalization.

Initial Experiment: A Small-Scale Model (~30M)

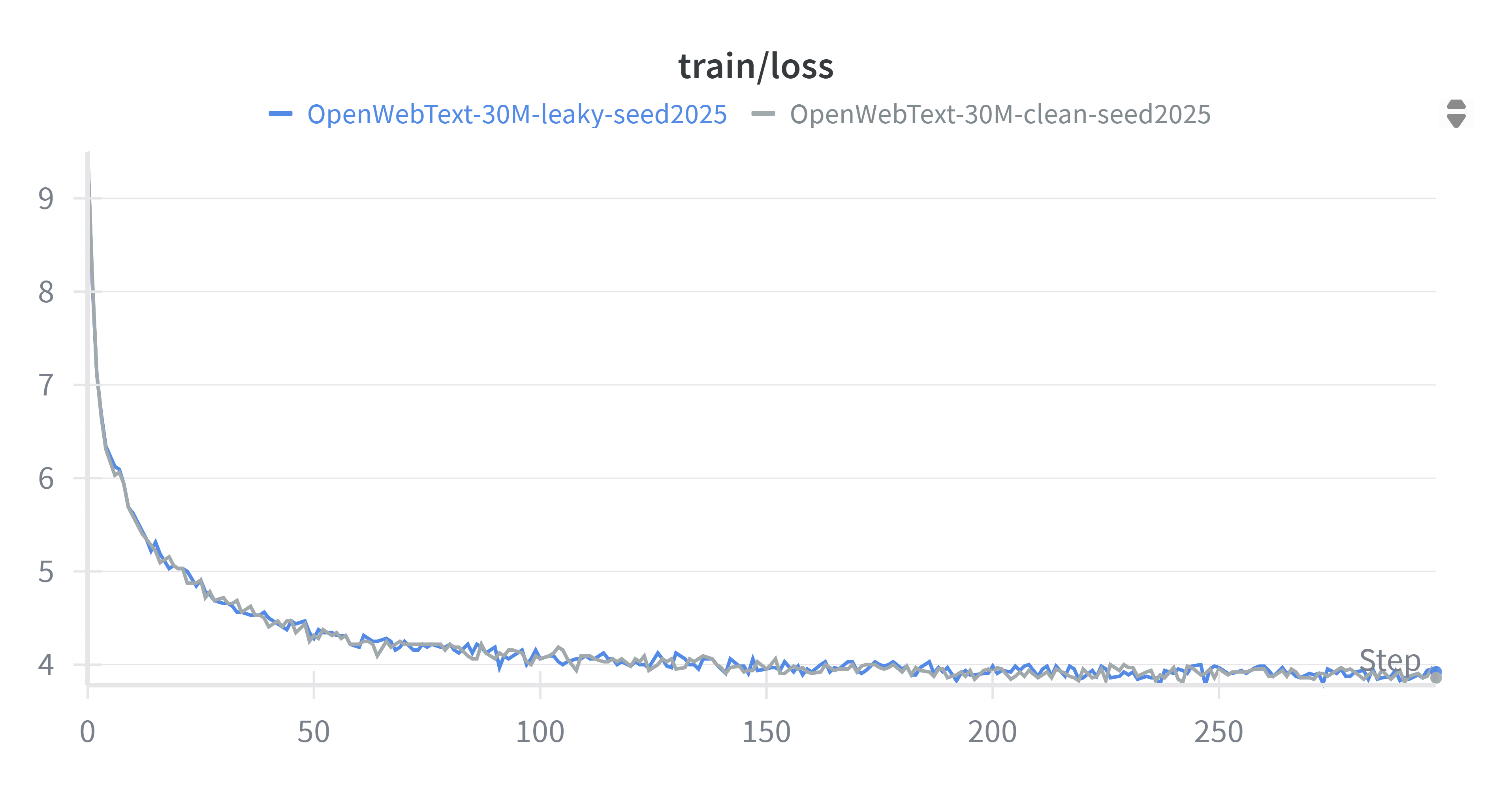

To test this, I trained two identical small transformer models (~30M parameters) from scratch:

- Model A: Used the "Clean" Tokenizer A.

- Model B: Used the "Leaky" Tokenizer B.

I trained both on the same training set and monitored their validation perplexity (). The validation curve showed that Model B consistently outperformed Model A during training.

Finally, I picked the best checkpoint for each model based on validation perplexity and evaluated them on the held-out test set.

figure 1: Training loss of 30M model (with Clean (A) and Leaky (B) tokenizer )

| Model Size | Tokenizer | Val PPL | Test PPL |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30M | Clean | 6.63 | 10.32 |

| 30M | Leaky | 6.64 | 10.31 |

Table 5: Results of validation PPL and test PPL using the 30M model.

TL;DR:

Validation perplexity differed by ≤0.01 and test perplexity by ≤0.01 (30M), within run-to-run noise. I only ran the experiment with a single-seed, multi-seed variance will be reported in Appendix once budget allows.

There's no sign of overfitting, the models performance was identical on both sets and tokenizer training did not lead to any observable leakage. This hypothesis is wrong, however results might differ at scale.

Hypothesis 3: Leakage results only show up at larger scales.

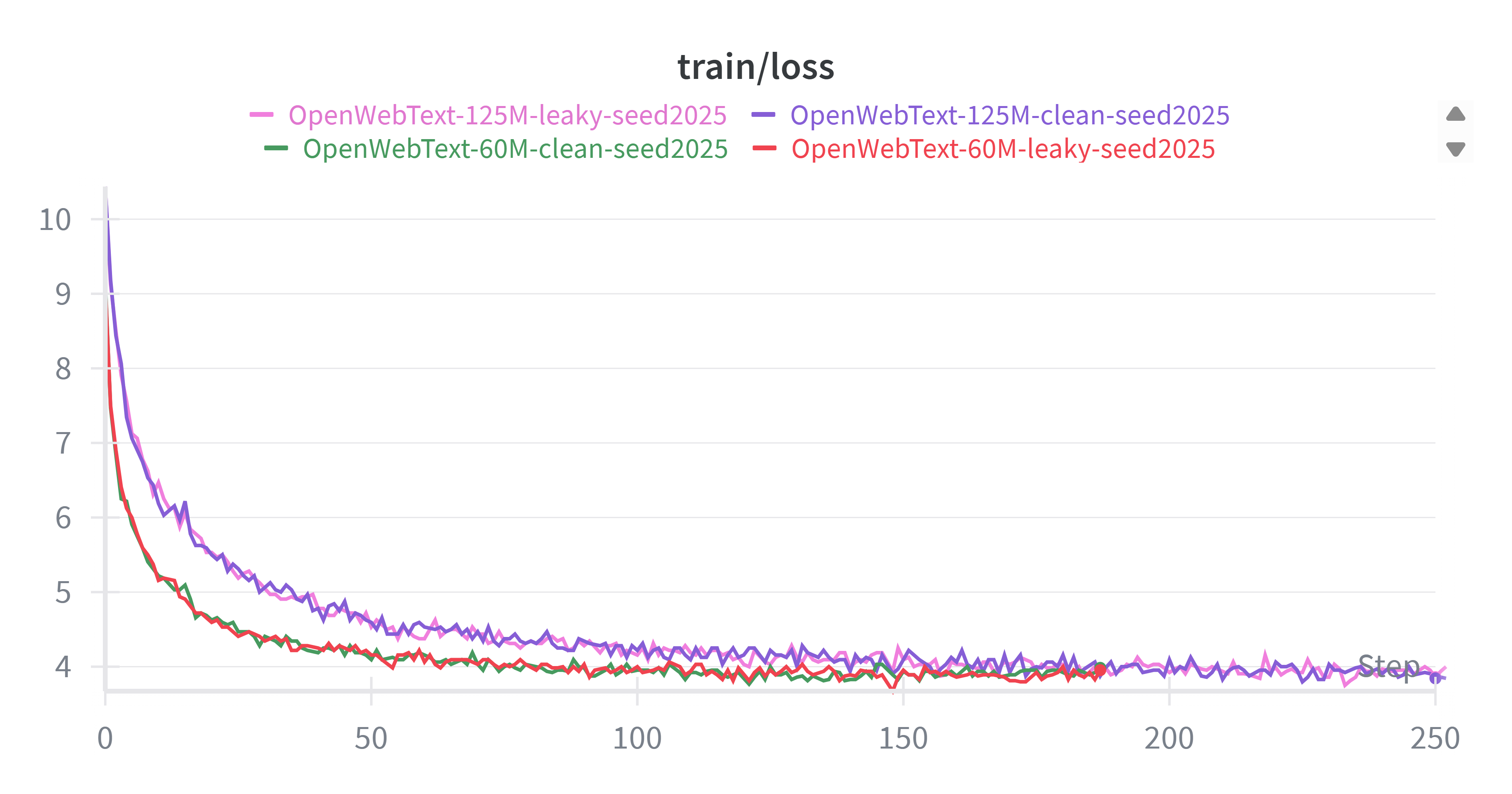

To test this hypothesis, I scaled to 60M and 125M within my Kaggle budget.

I scaled the training steps, learning rate and other hyperparameters to provide a fair comparison.

Figure 2: Training loss for 60M and 125M models.

| Model Size | Tokenizer | Val PPL | Test PPL |

|---|---|---|---|

| 60M | Clean | 6.15 | 9.80 |

| 60M | Leaky | 6.18 | 9.82 |

| 125M | Clean | 5.61 | 9.1 |

| 125M | Leaky | 5.68 | 9.2 |

Table 6: Results of validation PPL and test PPL for 60M and 125M models.

TL;DR:

Scaling to 60M and 125M did not reveal an effect: ΔTest-PPL ≤ 0.02 across sizes. Across 30–125M, test PPL is indistinguishable between tokenizers.

Interpretation of Results

BPE merges are dominated by high-frequency pair counts.

When Val is a small, in-distribution sample of Train,

adding Val barely perturbs those counts,

so the learned merges, and thus the segmentation, are effectively unchanged.

In other words, “exposure” at the tokenizer stage isn’t a strong shortcut when the distributions match and Val is small.

I validated this by both looking at the results from the tokenizer statistics and the metrics from training and validating models with different sizes.

Note again that my experiments used one seed, drawing conclusive results would demand further investigation.

Final Thoughts

This experiment began as a simple query into data leakage and although this is a simple idea and setup it proved to be very helpful in building my intuition into experimenting and going from questions to verifiable hypothesis to running experiments and finally interpreting results.

TL;DR for practitioners:

- Training your BPE tokenizer on

train + valis unlikely to bias validation/test PPL when both sets are large and in-domain.- If your validation set is small, out-of-domain, or you work with rare-token domains (code, biomedical), prefer train-only tokenizers or explicitly quantify tokenizer perturbation.

- if possible, run 2–3 seeds for critical comparisons, small Δs can otherwise be single-seed noise.

To reproduce the previous results, you can find the code for the implementation and experiments here: GitHub Repo

References:

- CS336 2025, Assignment 1 public repository.

- Hoffmann, J., et al. — Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models (Chinchilla).

- Sennrich, R., Haddow, B., Birch, A. — Neural Machine Translation of Rare Words with Subword Units.

- Aaron Gokaslan, Vanya Cohen, Ellie Pavlick, and Stefanie Tellex. OpenWebText corpus.